The Art of Cookery, Made Plain and Easy: Which Far Exceeds Any Thing of the Kind yet Published was a new kind of cookbook (as the title suggests) when it was first published in London in 1747. The cookbook’s anonymous author was “A Lady”, although it later shown to be written by Mrs. Hannah Glasse. In her preface to the reader, Mrs. Glasse opens with the statement “I believe I have attempted a branch of cookery, which nobody has yet thought worth their while to write upon…” The recipes were – for the most part – plain and simple, written with clear instructions.

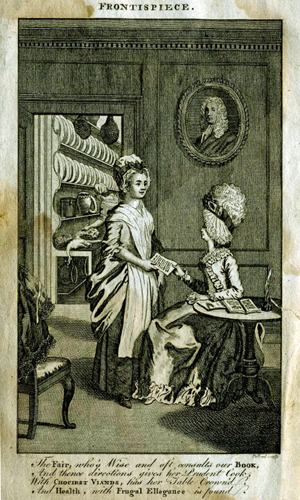

The frontispiece of the 1777 posthumous edition of

The frontispiece of the 1777 posthumous edition of

The Art of Cookery, Made Plain and Easy showing the lady of the house consulting her cook with instructions written down from the cookbook.

The cookbook was intended for the middle-classes and their servants, not for professional chefs or aristocratic households. The book was an immediate popular success, followed by numerous editions both before and after the death of its author in 1770. It became a major reference book for the home cook throughout the English speaking world in second half of the 18th and first part of the 19th centuries. The first American edition of the book appeared in 1801, printed in Baltimore.

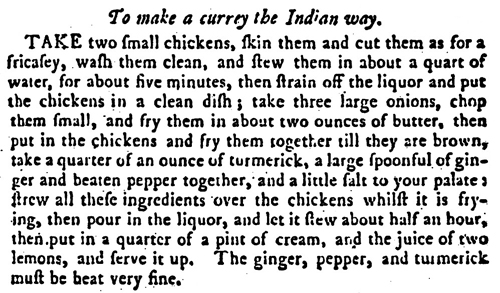

In addition to the “frugal elegance” promised in the author’s preface, one of the many interesting things about this cookbook you can see in the recipe above. The Art of Cookery, Made Plain and Easy contained new dishes brought into Britain as a result of the expanding control of the Indian Subcontinent by the London-based East India Company. The recipe is not an elaborate curry and most likely not an authentic Indian dish, but an early example of one modified for “colonial” taste and the availability of ingredients in Britain. In fact, it is quite possibly the first instance of a curry appearing in an English cookbook.

To Make a “Currey” the Indian Way

I recreated this recipe, updating the instructions and standardizing the measurements with slight modifications. It is a mild creamy curry, simply and lightly spiced, but it is IMPORTANT to note that the dish benefits by making it the day before to allow the spices to mellow. Serve with plain rice. Mrs. Glasse offers a “pellow” (pilau?) recipe made the Indian way after this entry, but it uses large amounts of melted butter (ghee?) to steam/cook the rice rather than water – entirely too much animal fat for modern consumption, particularly with a curry already rich with cream. It benefits with a garnish of chopped fresh coriander – an addition for the modern palate!

- 2-1/2 to 3 lbs. Chicken pieces – legs and/or breasts, skinned

- 3 cups chicken stock

- 3 large onions

- 2 Tablespoons butter

- 1 teaspoon ground turmeric

- 1-1/2 teaspoons ground ginger

- 1/2 teaspoon black pepper

- Salt to taste

- 1/2 cup cream

- 2 lemons

- fresh coriander for garnish

Melt the butter in a large skillet, sauté the finely chopped onions until they are beginning to brown, stirring frequently. Move the onions to the edges and brown the chicken pieces on all sides. Sprinkle on the turmeric, ginger, pepper and salt. Stir and let cook for a minute before pouring on the stock and bring to a boil.

Leaving it uncovered, lower the heat slightly and let it gently boil for an hour or more, until the stock is reduced to a thick sauce. Stir in the juice from the lemons. The lemon juice is essential as it does serve to cut the sharp flavors of the spices. Let it cook for 10 more minutes before adding the cream. Stir and let the cream thicken the sauce. Serve sprinkled with chopped fresh coriander.

Notes:

1. This post was inspired by the Georgians Revealed exhibition at the British Library in which the original edition of Hannah Glasse’s book appeared on display.

2. The 1774 and 1784 editions of Hannah Glasse’s book are available to download from the Internet Archive.

3. A similar curry recipe appears around 100 years later in the Illustrated London Cookbook by Frederick Bishop in 1852 (also available from the Internet Archive). There are two major differences: the addition of garlic and the use of a commercial curry powder instead of the turmeric, ginger and pepper. It seems likely, by this time, that curry had become standardized in English cuisine. This is also a decided improvement on the recipe with a smoother blend of spices.

4. The original 1740s recipe as well as that in Bishop’s book (see note 3) is surprisingly like the modern Coronation and Jubilee Chicken – a combination of chicken in a creamy sauce (or mayonnaise) flavored with curry powder.

I just love that you delve into culinary history! I’m bust modernising family recipes because I think nobody would be interested in them in their original, very plain form. Expectations about our daily fare has certainly moved on!

LikeLike

I love to see how things change over time and this recipe was an ideal choice for that as I was able to trace this type of chicken curry through the 19th century with the innovation of commercial curry powder and up to modern times with the ever popular Coronation Chicken. The 1740 curry had an interesting taste – not unpalatable – but not something that will go on the list of family favorites!

LikeLike

My experience with Coronation chicken was not pleasant I’m afraid, but then I’m sure it’s a much abused combination. It’s amazing in India how many English influences have found a permanent place in their cuisine too!

LikeLike

Colonial contact is always a two way interaction. There is a whole branch of archaeology that looks at this (naturally called Colonial Archaeology 😄). I am not surprised that this also affects food production. Coronation Chicken is very much abused – it is everywhere, including nasty pre-made sandwiches one gets at such places as Motorway Services and grimy urban pubs. But, it can be nice if done properly!

LikeLike

What an interesting post and a little glimpse into times past. Thanks for sharing!

LikeLike

Culinary history is a lot of fun! I was really excited when I spotted Hannah Glasse’s cookbook at the British Library exhibition. Glad you liked the post!

LikeLike

So did you like the taste? It sounds like something some of my English friends would love to eat!

LikeLike

It was unusual! An interesting experiment and not completely inedible, but I think there is a reason why commercial curry powder was used in similar, later recipes.

LikeLike

For sure, a great experiment though!

LikeLike

You are unique! …i loved what you did here, love old cookbooks and you discovered and made a recipe i really would love to try!

LikeLike

I saw the cookbook on display at an exhibition at the British Library, so can’t take the credit for discovering it and its connection to curry. But, it was fun experimenting with the old recipe even though I came to the conclusion that commercial curry powders (a finer, smoother blend of spices) were invented for a reason!

LikeLike

My favorite subject. That ‘curry’ is a British word and a British dish. Not Indian. At some point I will write about this.

LikeLike

It is a great subject. I’ll be very interested to hear what you have to say. I’m posting another “Colonial Curry” post soon – although a bit more up to date than the 18th century. You are right, they are definitely not authentic Indian dishes!

LikeLike

“Interesting and not completely inedible” describes many of my experiments with 18th-century recipes! I love the frontispiece of Glasse’s book. Both the lady of the house and the cook look so elegant, don’t they? Thanks for the great post.

LikeLike

I remember your post on posset experiments! Yes, always a risk when recreating old recipes. The curry was fine, but the flavors were initially sharp and really needed to sit overnight to mellow. I loved the image as well – it’s an out of copyright image I found on Wikipedia about Hannah Glasse and the cookbook. The hairstyle of the lady of the house is amazing.

LikeLike

How cool is that?? The history is so interesting, thank you for sharing the book and the recipe x

LikeLike

Thanks! Got more similar type books… Am thinking of adding a section to the blog on historical foods and cookbooks…

LikeLike

That sounds like a fab idea..

LikeLike

[…] ← Colonial Curry: 1740s Style […]

LikeLike

[…] of savory dishes made of a mélange of onions, ginger, garlic, coriander, cumin, and turmeric. As this blog post explores, cookbooks from the seventeen hundreds had started to experiment with Indian ways of […]

LikeLike